In this day and age, if you write to the Chairman of a quango or the CEO of a company or the Secretary of State for a department, you expect that the letter will be intercepted by “a secretary” or something similar, and will then be routed to someone else in the organisation to deal with - sometimes a specialist complaints unit, but more often back down to the call centre you were stuck trying to get satisfaction from in the first place.

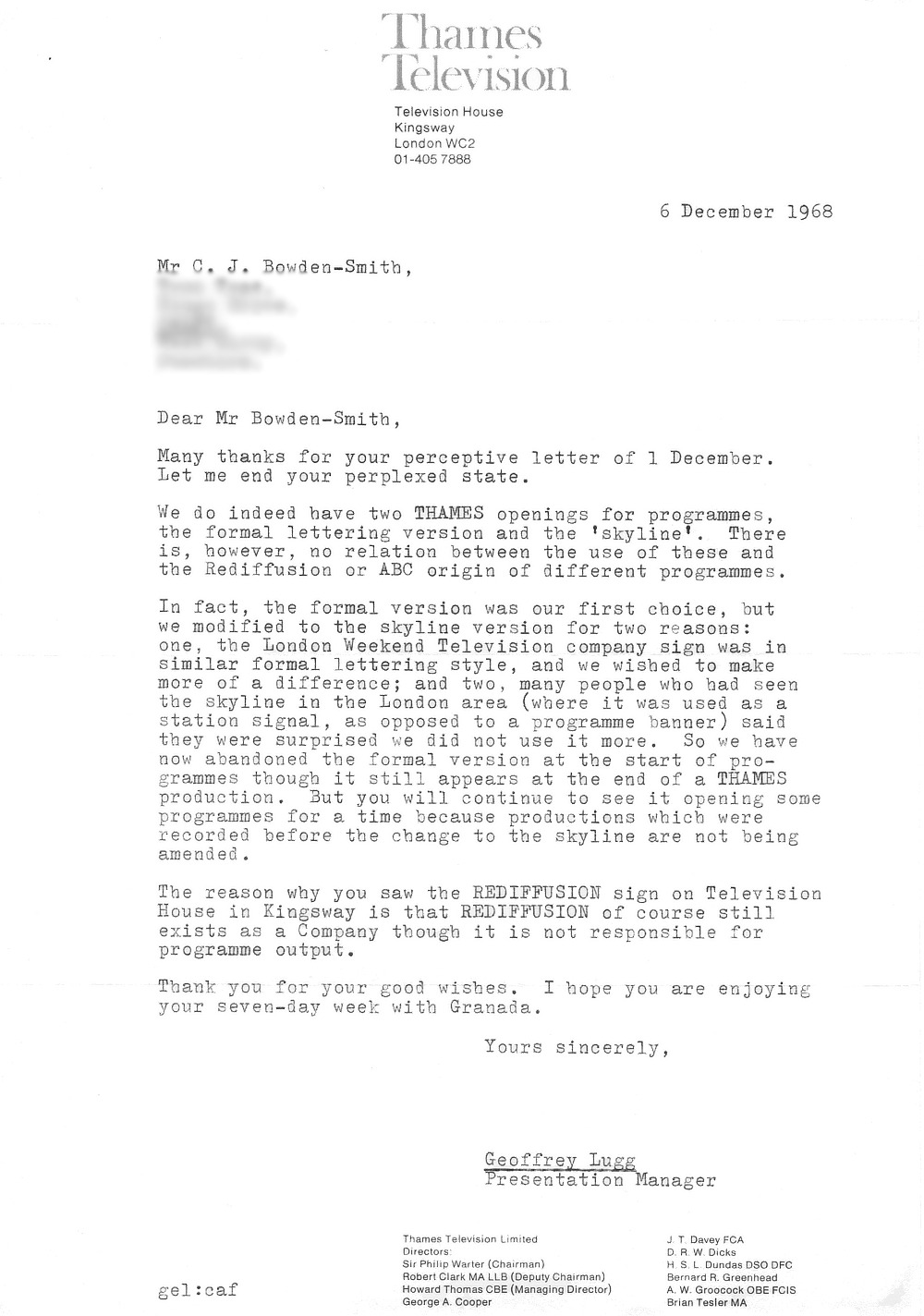

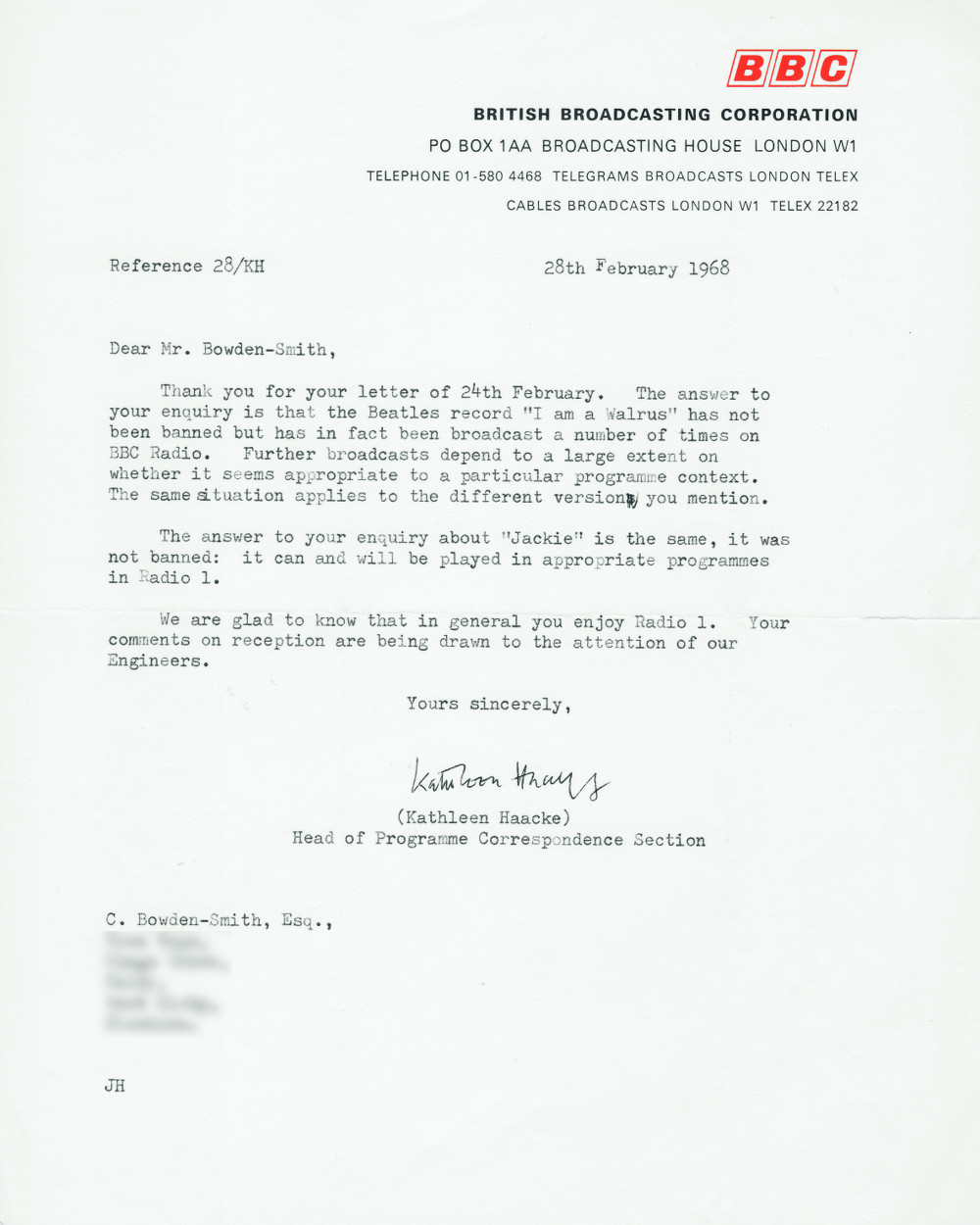

Not in the 1960s. If you wrote to someone up top in an organisation, they would most likely see the letter themselves and write back; if not, they would pass it down to someone senior with instructions that a full reply be given and the resulting letter would begin with an apology that the head honcho was not the one to reply.

Here we’re writing to the Independent Television Authority in the immediate aftermath of the announcement of the forthcoming contract changes. And lo and behold, despite being the busiest he has ever been in this job, the Chairman himself replies to the letter we sent him.

Our idea was that TWW could survive after all, if it was given St Hilary Channel 10 and the Ridge Hill transmitter, creating a tight little ‘West’ region. Harlech could then continue on St Hilary Channel 7 and the former Teledu Cymru transmitters. In theory, it sounds like it would work.

In practice, it fails due to politics and finance.

The politics was at the ITA. Lord Hill of Luton had been stung by the 1964 contract round, where he wasn’t able to make any changes and was treated with outright arrogance by several of the incumbent contractors. He vowed that 1968′s changes would be different, and privately decided that a big company would be for the chop - a real reminder to all of them that they were there at the Authority’s pleasure.

The one for the chop was to be STV, but their competitor, the Grimmond Consortium, was terrible. Meanwhile, TWW’s competitor was good on paper. So TWW were the political sacrifice.

The finance issue was to do with overlaps and the Authority having got its fingers burnt in 1964 when Teledu Cymru collapsed. There was not the money for a full service in two languages from just west and north Wales. Adding the largely English-speaking south of Wales almost made it viable, but if the Welsh contractor faced competition from an English-language only incumbent who had already tied up most of the advertising contracts, the Welsh contractor would be bound to fail… again. This could not be allowed to happen.

We didn’t see this then, and Charles Hill didn’t, of course, explain it to us either, but in retrospect, he was right.